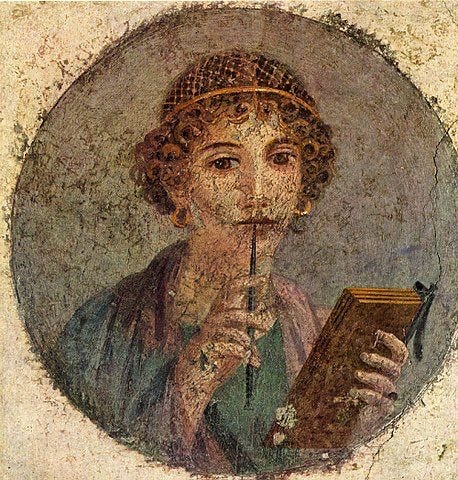

This morning, as I searched through papers I wrote during my undergrad for a potential journal submission, I came across this sweet essay from February of 2023 that I wrote for a Comparative Literature class. It’s about the ancient Greek poet Sappho, a character that I find impossible not to love.

Sappho was a Greek poet from the 6th century BCE who is known for her lyric poetry. Little is known about her life, and most of her poems are fragments. As most girls from wealthy families, she was sent to a school formed by a community of women on the Isle of Lesbos, where they gathered to read poetry, perform music, celebrate women’s religious festivals and welcome their daughter's first menses. During this period of Greek history, homosexuality was accepted and relationships between women on the island were common. (And yes, the terms “lesbian” and “sapphic” were most likely introduced because of her)

Sappho's style is graceful and elegant, and she often writes about unreturned love, longing, erotic passion, and memory. Sappho’s writings were criticized and ultimately destroyed by the church after the 4th century because of the erotic and lesbian imagery. Attempts to revive her poetry began in the Renaissance and have continued throughout history.

Perhaps Sappho’s most famous work is “Ode to Aphrodite”. There are many translated versions of this poem, and I chose this one by David A. Campbell mainly because I found it to be one of the easiest to read: Ode to Aphrodite

Now that we have done the introductions, here are my reflections on Sappho’s use of memory as a way of working with absence, and her bold validation of women’s private and erotic concerns that ultimately tweaks the traditional male perspective on the narrative of epic lyrics.

(This is a very academic read and might not be for everybody. And that’s okay.)

Memory, Desire and Absence in Sappho's lyrics

The tradition of Greek epic is founded on memory. The greatest epic composers, such as Hesiod and Homer, were certainly not eyewitness accounts to the stories narrated in their works, and rather just the minds behind a compilation of mythological and fictional origin stories that echoed through the memory of Greeks at the time. Memory existed not just as the mere act of remembering but also as a way of making sense of the world and its origins, and to create a bridge between mortal men and gods. The Archaic Greek poet Sappho, also known as the "Tenth Muse", from the island of Lesbos, has been noted to place special emphasis on memory as a core element in her lyrics, most of which are love poems. Sappho's notion of memory is strongly associated with feelings of desire and absence, and usually directed at women and/or goddesses. Given the uniqueness of her character and poetry, in this essay I aim at discussing Sappho's use of memory as a way of working with absence, and with her desire for things and people that, according to societal norms, were unattainable for women at the time. By doing so, she validates women's private and erotic concerns and tweaks the traditional male perspective on the narrative of epic lyrics.

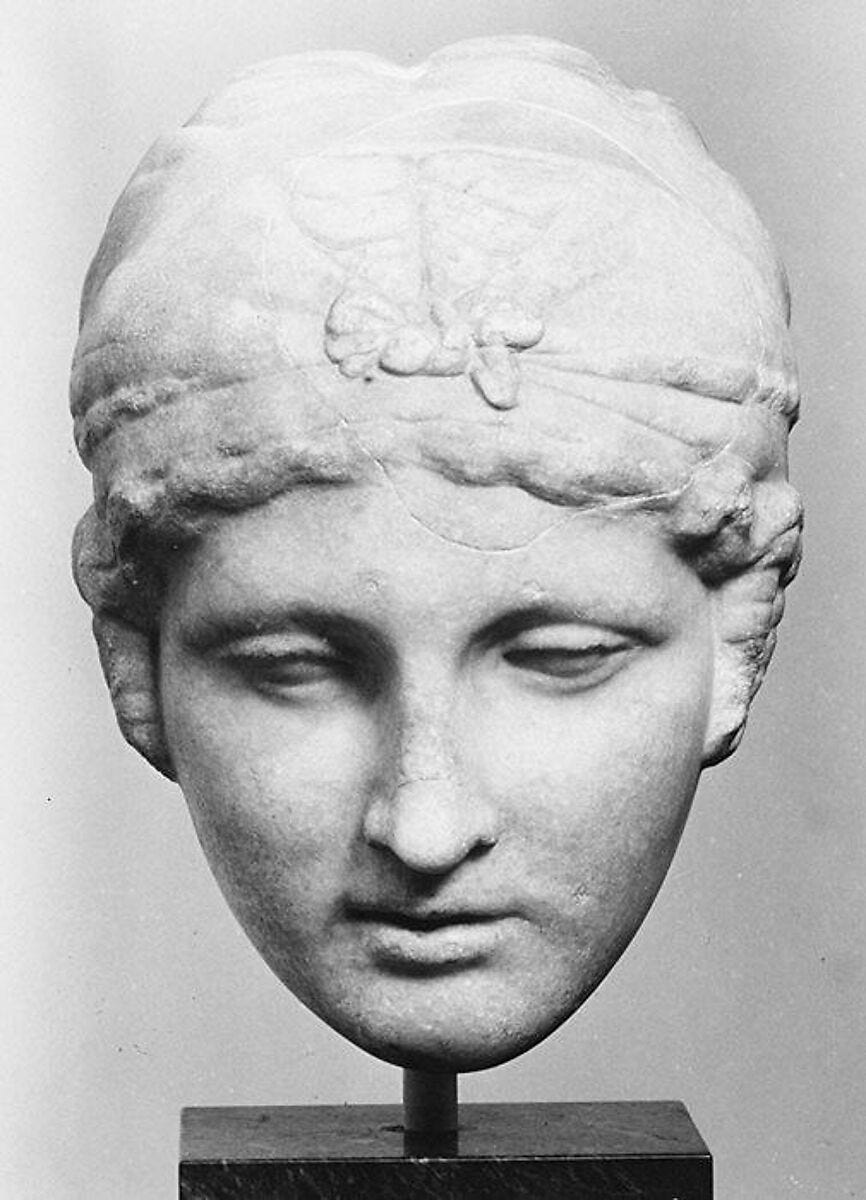

Sappho's Fragment 1 is addressed to the daughter of Zeus and Greek goddess of love and beauty, Aphrodite. The poem is introduced with Sappho as the speaker invoking Aphrodite, a practice that was common in epic tradition but usually done by male heroes. The tone of the dialogue between Sappho and Aphrodite is intimate and suggests that Sappho has asked for the goddess' help in the past and succeeded in her endeavor. She pleads to the goddess to not to "crush her heart with longing", with which Aphrodite in the poem promptly replies "Who, Sappho, / is doing you wrong?". The goddess not only responds to the girl, but also caters to her needs and promises that whoever wronged Sappho will soon regret their actions. Fragment 1 is incredibly memorable because it is a fresh perspective and deliberate response from Sappho to the male world of war and to a specific episode of the Iliad, which was frequently recited at the time in public festivals. The difference lies in the fact that instead of invoking a goddess to aid with warfare or politics, Sappho does it in regards to her own sentimental matters. Sappho's narrative, along with Aphrodite's response in the poem, legitimizes Sappho's private concerns to the same level as it would to a hero's adventurous or bellic ones. She places her life and love at the center of a narrative that was traditionally exclusive to what were deemed male dealings. Furthermore, Sappho chooses Aphrodite to be her ally in this enterprise and by doing so, depicts an image of the goddess of love and beauty as strong ally, as opposed to the mocked image of Aphrodite painted by Athena to Diomedes according to Book Five of the Iliad. Fragment 1 is portrayed from the perspective of the author remembering her encounter with Aphrodite, thus in a metaphysical space that doesn't necessarily exist in the material world. Because of societal and epic norms of the time, Sappho as a lyricist would never be able to invoke a goddess to aid her in the matter of passion and desire, especially towards another woman. The fact that this encounter takes place in the realm of memory could be interpreted as Sappho's own creation of a sphere in which she is allowed to partake in these actions.

Memory is known to be a vital force in the interaction between mental experiences and social systems of exclusion and discrimination, among others. During the time of Sappho's life, despite her possibly having been able to experience more freedom than latter Athenian women, women were confined to gender-segregated, secluded parts of the house and certainly could not take part in political and public decisions. In other words, women were able to occupy very limited spaces, and were mostly confined to the household (oikos) while men were allowed in the public sphere (agora). Upon analyzing what remains of Sappho's poems, it is noticeable that the vast majority of them are set in the outdoors, and never in the domestic sphere. In Fragment 96 the landscape is luscious and erotic, and there is a clear delimitation between what seems to be the male and the female world. While the daylight belongs to male concerns, the night creates a space where two women can be together, and the only space where they can do so in a romantic way. Just as Sappho bends norms of Greek epic by evoking goddesses despite not being a traditional hero, she also stretches and plays with the limits of the public and the private sphere, and the masculine and feminine spaces in Archaic Greece. The same fragment contains an epic simile that directly cites Homer's "rosy-fingered moon", an act that can be interpreted as Sappho taking ownership of the narrative and putting forward her own version of epic lyrics. Sappho as a woman and as a composer uses both memory and imagination to shape a third, metaphysical sphere in which she can occupy male-designated spaces, meaning not only the public but also the epic genre. In her memory, and in her own poetry, she is able to fantasize about sensuous landscapes and a freedom that she could never possess in the physical world.

The Odyssey makes up for an interesting comparison of how Homer, as a male poet and contemporary to Sappho, decides to treat the theme of memory in his work. In the ten years in which Odysseus wanders the Mediterranean he is fueled by memory and his desire to return to his homeland. In his adventures, he encounters many threats on the path to his final destination, and a series of them relate directly to his memory, as an example his encounter with Circe in Book 10. The enchantress gives Odysseus' men a potion that erases from their memories any thoughts of home, and she then transforms them into swine. According to Marissa Henry in her essay "Witchy Woman: Power, Drugs and Memory in the Odyssey", Circe's use of drugs, along with the example of Helen, "complicates the function of memory, which comes to appear as a frightening pliable measure of reality". She states that the appearances of memory drugs, combined with other situations in the text, operate "to create broader impressions of the uneasy relationship between men and gods and of the main character with respect to morality and to gender dynamics". In a completely different, yet similar, manner to Sappho, Circe is able to make the concept of memory malleable and to shape the narrative according to her perspective and needs. The main difference would be that despite the effects of Circe's potion, the reader eventually finds out that Odysseus, as opposed to Sappho, does indeed make it back home, or to the place of his "memory".

Sappho's Fragment 16 offers another important example of the poet's ability with bending the limits of the Greek female and male spaces. The first stanza opens the poem with imagery of objects related to war, thus deemed masculine, as the "loveliest thing / on the black earth". But the tone suddenly changes and she writes that according to her the loveliest thing is "what you desire", and she uses Helen, the "woman who far surpassed / all women in beauty" as the clear example for her broader point. Helen of Troy, who gave up her husband, daughter and parents to be with Paris and thus indirectly caused the Trojan War, is here not only validated but praised by Sappho in her lyric. Similarly to what she did to Aphrodite in Fragment 1, by using memory to remember Helen from a perspective that was different from Homer's ambivalent one, Sappho places emphasis on the "power of true love" and the emotions of women and goddesses thus placing their issues at the same level of relevance as conventional heroic pursuits.

In the same poem Sappho concludes with the memory of "Anaktoria / who is elsewhere", a presumed lover of hers. Anaktoria existing in the poem only in the form of a memory poses again the hypothesis that this might be because Sappho needs a third sphere in which she and said woman can coexist freely as lovers. The poem concludes with Sappho's strong position that she would rather "see her comely step, / the shining luster of her face" than the "Lydians' chariots and infantry / in armor". Sappho, a young woman, teacher of girls, married and a mother, states how much she would rather watch her lover materialized in front of her, away from the realm of memory, than classic exhibits of masculinity.

Ultimately, Sappho as the head of a female circle, a poet and an aristocrat woman occupied very limited spaces because of her gender. The fragments of her poems that have survived to this day shows that the fluidity of Sappho's sexuality equipped her with an even deeper and more intricate understanding of the dynamics of gender roles and sexuality in Greece at that time. Surrounded by narratives that placed male concerns at the forefront of relevance, she used her voice as a poet to shift the lenses of her lyrics to validate concerns that were private and personal to her. Sappho's extensive use of memory in her works offers the possibility of her need to craft a metaphysical domain in which she would be free to, and act upon, desire.

Thank you for making it this far. I hope to see you here again soon <3

Xx

lovely

long live sappho